WOMEN’S EXPERIENCE

Tyumen and Tomsk region

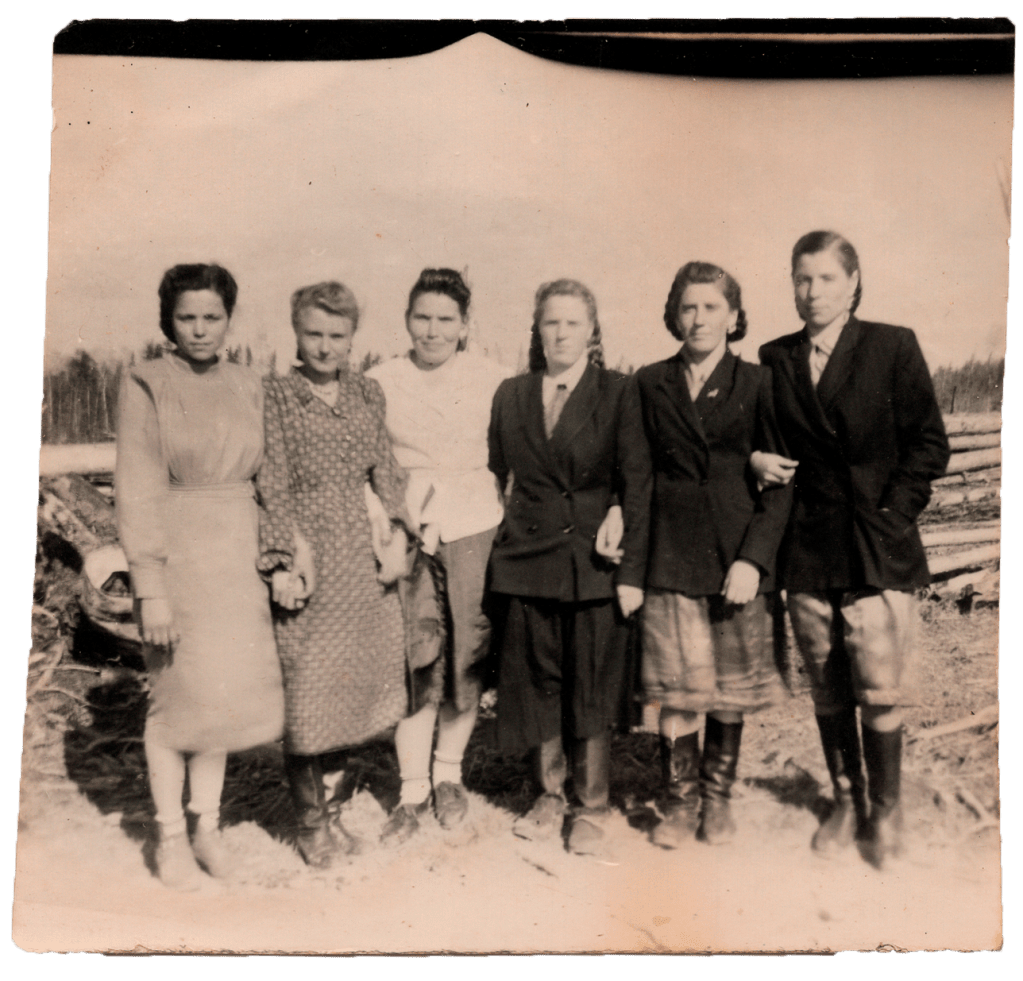

Vasylyna Yakibyuk (third from the right) with her friends at a logging site in the Tyumen region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Vasylyna Yakibyuk

vASYLINA YAKIBYUK

deported in 1951 to the Tyumen region

Everyone was after me, all kinds of educated men. They wanted me. And I said: ‘We have the Hrepinyaks here, the poor people that we went to school together. I will go home when we have the releas, and marry the Hrepyniak. I don’t want anyone else!’ And I didn’t want anyone. The boys crowded. He would approach, make a move towards me, and I would punch him in the face. I would slap in the face so that they said: ‘Don’t approach that girl.’ — ‘Why?’ — ‘She punches in the face!’ I was a smart filly, and I would not give in. I didn’t want anyone. There were Ukrainians, there were men to marry. But I didn’t want to.

A special settler with a chainsaw at a sawmill in the Tomsk region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Vira Tsvyk (Borovets)

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

Women accounted for almost half of the total number of deportees from Western Ukraine. According to 1951 data — there were 68,287 people. Given the ratio between able-bodied men (24%) and women (45%) among deportees, as of July 15, 1949, the gender balance in heavy production was quite obvious. They were forced to do hard work in the forest industry, and often they had to do logging. Similarly, in the coal industry, women were even involved in mining works underground: they would load rocks or push the trolleys. In addition, some of them recount sexual harassment from production directors. Women’s stories were also closely linked to the experience of motherhood, as many were deported with children or had their babies already in special settlements. Between 1945 and 1950 alone, 2,181 children were born to families deported from Western Ukraine. It was only in 1958 that the deportation of pregnant women and those with children under the age of 8 was officially abolished in the Soviet Union.

Beruta Kartanaite, with her daughter Vira, village of Karelino in the Tomsk region, 1954

Source: Private archive of Vira Kipran (Moskva)

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

In the group photo, we see six young women holding their hands tight. The high midday sun dazzles their eyes and highlights their facial features. In the background, we can see a logging site. However, they pose not in work clothes but in beautiful holiday outfits. What was the reason for taking such a picture? Any special event or just the presence of a photographer, combined with the desire to capture the current moment? What is the relationship between the people we see here? What else do they share in addition to the fact that they found themselves in a special settlement against their will? The answer to these questions is beyond the scope of the frame, and where there is no person who remembers, we are unlikely to know the broader context.

Is this photo a representation of a woman’s experience? Partly it is. We can see what clothes the women wore in the special settlement, what their living space looked like, what hairstyles, jewelry, etc. they had. If we understand “women’s experience” as certain survival strategies, as a process stretched over time, or as a set of decisions made by women in certain circumstances, then it is another category. Its reflection goes beyond the representational capabilities of the photographic medium. How were the problems of female hygiene, pregnancy and childbirth were addressed? How did women deal with security issues? How did they combine the birth and upbringing of children with hard work and living? We are unlikely to learn about all this from amateur photographs. They can rather serve as an illustrative addition to scientific research, eyewitness accounts and an intermediate link in establishing an emotional connection with their stories.