OUTFITS

Kemerovo region

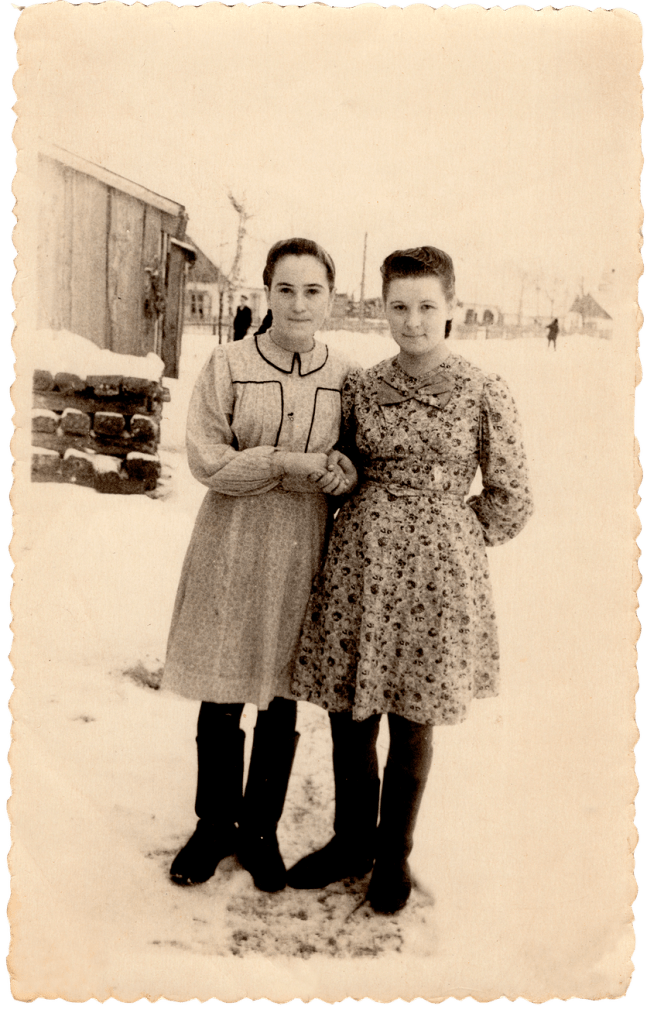

Yevhenia Radovets (left) with a friend, Prokopyevsk city in the Kemerovo region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Mykhailo Kutsyaba

mYKHAYLO KUTSIABA

who fled during the deportation in 1947, was forced to leave for the Kemerovo region in 1951

[My wife’s name was] Radovets Yevhenia, Mykola’s daughter. She lived in Sokal region, in Bobyatyn. Then she was taken there [to Siberia] because her father was in the UPA. He was put to jail, imprisoned. He had 15 years of hard labor. The wife worked in a tailor’s shop; when she returned to Ukraine, she didn’t work for a year and a half, and then, when the Sokal hosiery factory started recruiting workers she went to work at that factory.

Yevhenia Radovets (center) with friends, Prokopyevsk city in the Kemerovo region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Mykhailo Kutsyaba

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

The clothes in which deportees from Western Ukraine arrived at the places of special settlements were not adapted to the local climate – “Volyn boots proved unsuitable for the conditions of Siberia,” as they themselves used to say. However, special settlers were forced to use them for a long time because it was impossible to buy anything in the store. The supply of clothing, like all manufactured goods, from 1944 to 1947, remained strictly limited to the card-based system. Some made the outfits from old pieces of cloth, parachutes, curtains, military equipment, or from repainted worn-out clothes. According to the established rules, in the mining industry people had to be provided with overalls through the departments of labor supply. This was mandatory but only partially implemented. In the report of the NKVD of the USSR on the situation with employment and provision of special settlers, of April 26, 1945, we can read: “The needs of special migrants in clothing and footwear are extremely high. People do not go to work because they lack clothes, children do not go to school.” The report dated June 25, 1947, by the head of the Sverdlovsk Region Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs stated: Only 28% of working migrants have leather shoes, and 17% have felt boots.

Yevhenia Radovets (third on the right in the first row) among friends, Prokopyevsk city in the Kemerovo region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Mykhailo Kutsyaba

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

It is quite difficult to get a complete impression from archival photographs of how the deportees dressed in everyday life and what was available to them, because people dressed the best to pose for photoes. We see that both men and women often posed in embroidered shirts, which they certainly did not wear every day. The clothing in the photos rather emphasizes the efforts of the deportees to preserve their identity or create an atmosphere suitable for an event.

In the photos, dresses and skirts are often combined with high boots that are comfortable to walk in the snow and off-road. Or, people pose in beautiful clothes that clearly do not suit the weather – please, pay attention to the photo where girls are posing in light dresses outside, in a snowy yard. Also, even when people had the opportunity to get new clothes, any wide choice of fabrics or styles was out of question. For example, in a photo taken in the studio against the background of a painted landscape, we see women dressed in identical coats. In another group photo, we also see the same fabrics and repetitive styles.On the other hand, such photos were often taken by a family member, and then either found their permanent place in the album of the same family, or sent to relatives. Deportees often sent photos to relatives who were in Ukraine or in Gulag camps. Therefore, according to their photo owners, they were intended for important eyes. That is why the opacity of the vernacular archives serves as a kind of protective layer from prying eyes, including researchers.