MALE EXPERIENCES

Tomsk and Kemerovo regions

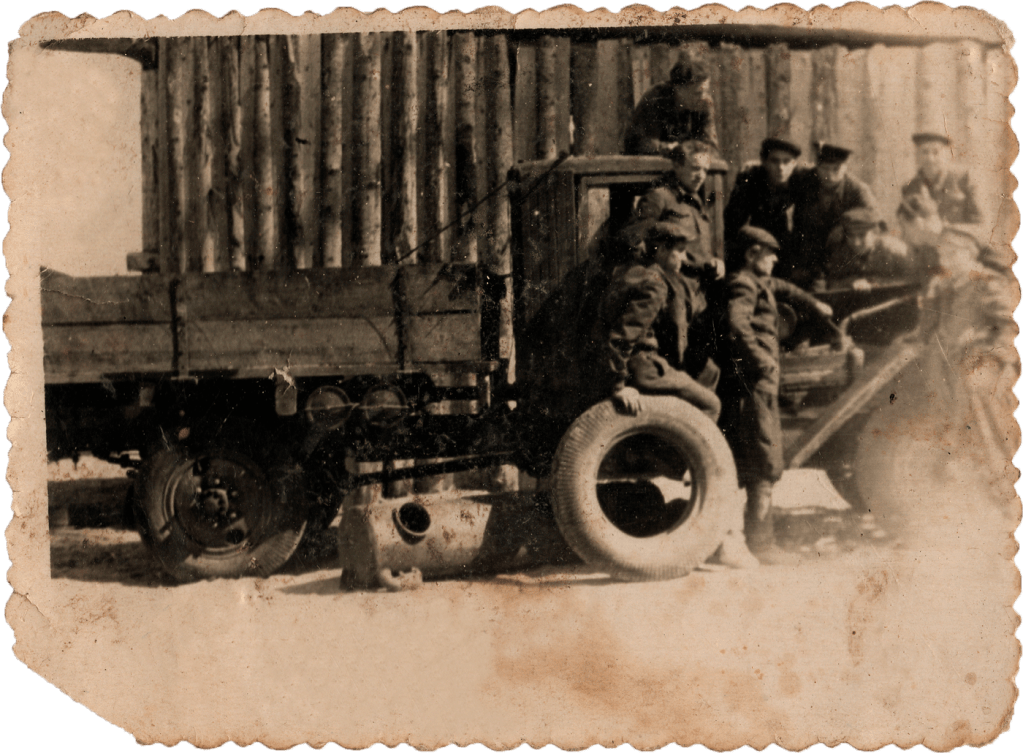

Special settlers near the truck, Torba village in the Tomsk region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Vira Kipran (Moskva)

mARTA VVEDENSKA (HULEY)

deported in 1950 to the Tomsk region

We went to work on the collective farm. When a tractor is sowing, plowing, or ploughing something, someone needs to watch it. So, my brothers went there. A younger brother [Ivan], he was ambitious, smart, and studied well. He was so depressed, you know, from the fact that he had to go to the collective farm and watch that tractor. When my mother saw it, she thought that he might do something to himself, God forbid.

Stepan Prytula (first from the left in the first row) with colleagues in the construction team, Prokopyevsk city in the Kemerovo region, early 1950s

Source: Private archive of Stepan Prytula

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

According to 1951 data, there were 37,047 men among the special settlers from Western Ukraine, which is a little more than a quarter of the total. Even fewer of them were of working age. Therefore, they were in especially high demand in heavy production. The commanders of special settlements selected among them the so-called elders, seniors, and ten-house-chiefs. They were in charge of order in the settlements that were divided into sections, dormitories, and barracks. They were appointed for every 30 special settlers and they were obliged to report to the commandant every ten days. Some of the men joined their deported families after demobilization from the Red Army. The male population of special settlements began to increase steadily with the beginning of the release of Gulag camp prisoners. Young men taken away as children in the first years of mass deportations also grew up. The gender balance started changing. Consequently, the number of marriages and the birth rate increased.

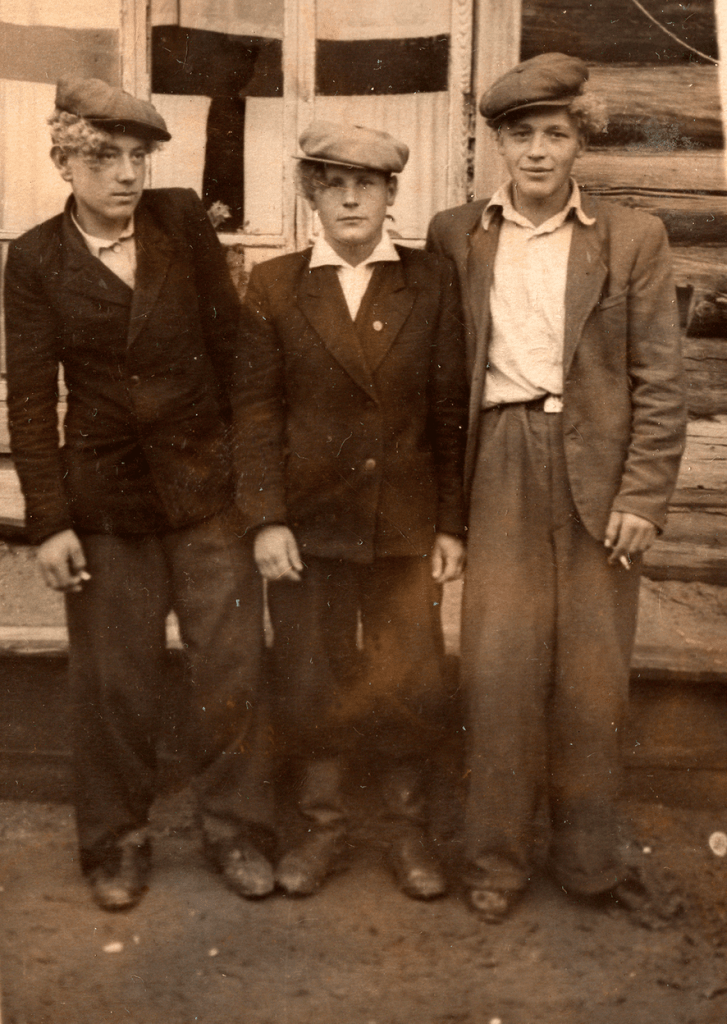

Mykola Tsvyk (first from the right) with his comrades, Tomsk, early 1950s

Source: Private Archive of Vira Tsvyk (Borovets)

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

The abandonment of previous plans for the future and the narrowing of the expectation horizon for basic needs, reducing a person to the physical capabilities of their body and the stigma of deportation, in addition to direct impact on life, also create strong mental pressure. Masculine stereotypes, such as the requirement to be strong under any circumstances, to provide the family with all things necessary, not to complain, not to give up, not to show their emotions, — in extreme conditions they can produce an additional mental strain.

On the other hand, forced relocation can not only reinforce traditional gender roles but also undermine them. In fact, in the absence of one family member, the other one had to assume their responsibilities. Among the deportees, there were many women with children, so the boys had to grow up early and take on the responsibilities and work of adult men. Researchers say that men can respond to the traumatic challenges with depression, alcoholism and the escalation of violence against women, in public and in private settings.

In one of the photos, by the way, we can see a man in a woman’s jacket again.