life before

Lviv

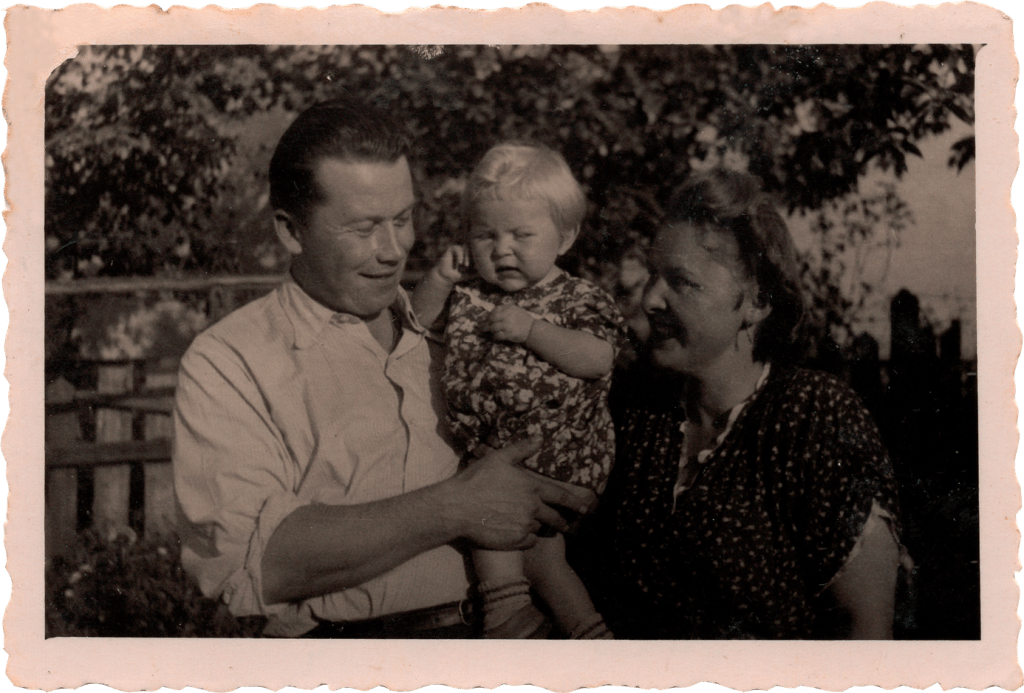

The couple of Mykhailo and Olha Tymovchak, with their daughter Lesya, Lviv, 1950

Source: Private archive of Lesya Tymovchak

LESIA TYMOVCHAK

deported in 1950 to the Tomsk region

[We used to live] in Lviv, at Novoznesenska, 81. The house still stands there. It was our house, my grandparents built it all with their own hands. Two-storey. There was also a store, a private business. Mom and Dad always helped ‘our boys’ — they provided medical care to them. Apparently, someone was watching. That’s for one. Secondly, our self-sufficient position was also a pain in the neck to some. We already thought we would not be affected because it was the time of some final deportations. On the very day of the Protection of the Virgin, in 1950, they came at night and said: ‘Get ready!’

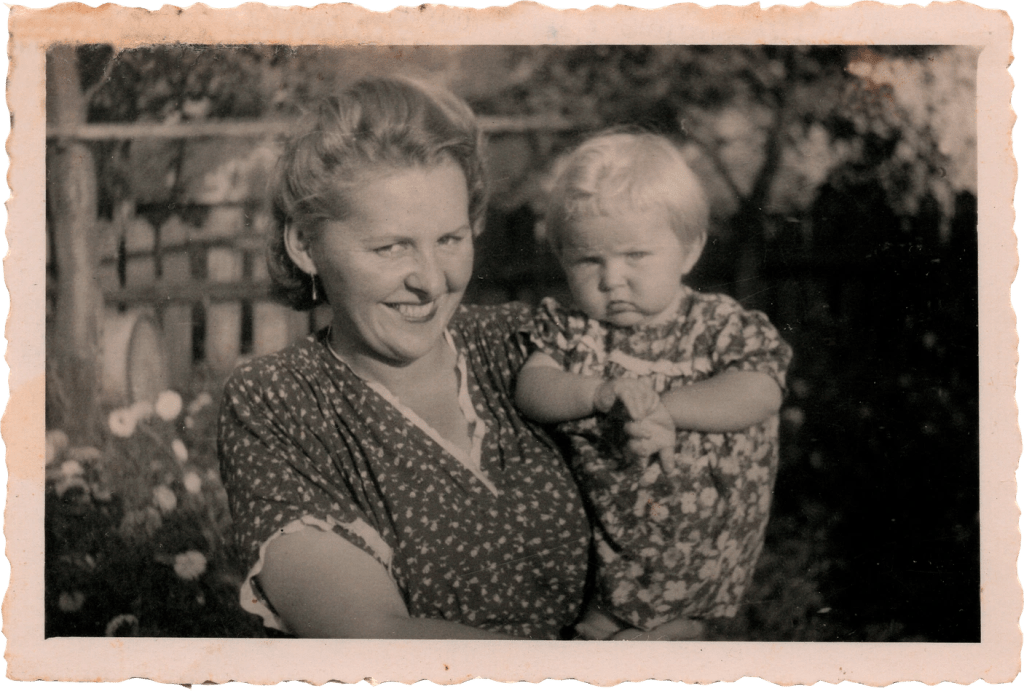

Olha Tymovchak with her daughter Lesya, Lviv, 1950

Source: Private archive of Lesya Tymovchak

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

Although the population of Western Ukraine had no illusions about the Soviet regime after 1939, for many people the mass deportations came as a complete surprise. They were prepared in top-secret conditions. In villages and towns, the process began with the compilation of lists of families to be deported. They were included on the grounds of the appropriate ‘evidence base’: information from village councils or operative units of the NKVD / KGB about the person’s affiliation to the anti-Soviet resistance, as well as the testimony of fellow villagers. It was strictly forbidden to include into such lists the families of Red Army servicemen or persons who turned themselves in. However, the guidelines were often broken. Sometimes, the information about arrests leaked from the executors, especially in the village settings. Then, whole families managed to escape. However, most people learned about their deportation only when the perpetrators had already broken into their homes.

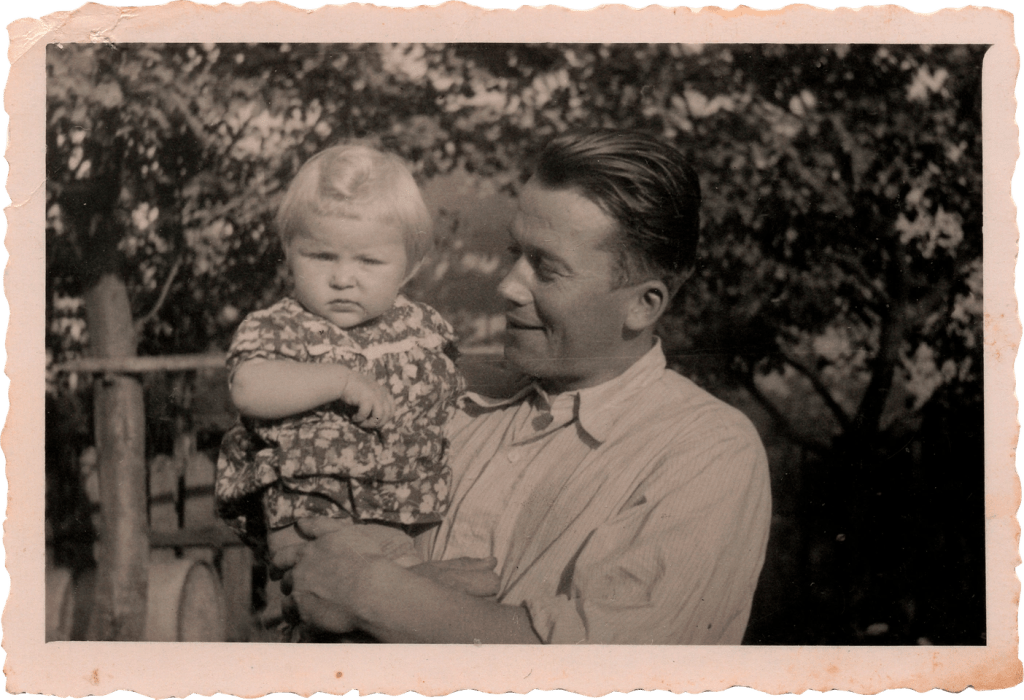

Mykhailo Tymovchak with his daughter Lesya, Lviv, 1950

Source: Private archive of Lesya Tymovchak

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

These photos were taken just a few months before the deportation. From them we do not learn any significant details of family life before the exile – we can only see the clothes, hairstyles, flowers and trees in the garden, and a fragment of the fence. However, these pictures create a special space of nostalgia, and serve as a kind of interstice. When you looking through it, you can establish an emotional connection with the world that existed before the Tymovchak couple and little Lesya were deported.

It is also important to consider various aspects of the circulation and preservation of these photographs as tangible objects. Because the practices associated with the material measurement of vernacular archives actually establish the space of memory. How have these photos survived to this day and why did they survive? Where were they kept when the family was in Siberia? How often did they look at them? What did they tell about the photos and to whom? Did little Lesya see them growing up? What happened to these photos when the family returned to Ukraine?