housing

Tomsk and Khabarovsk regions

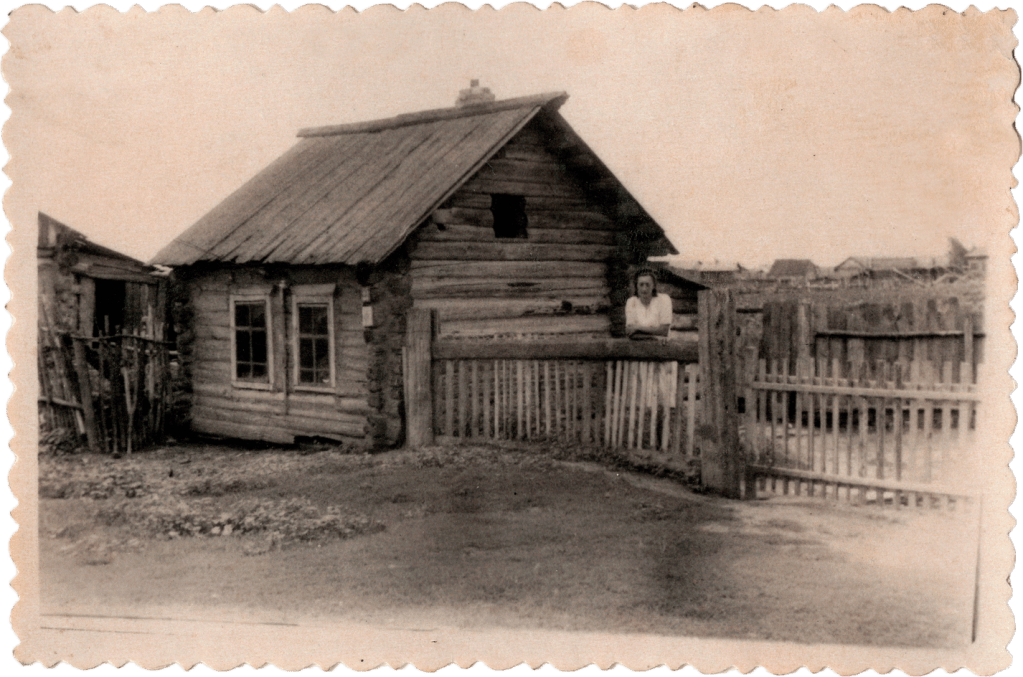

Special settler Maria Hulei near her house, Zyryanske village in the Tomsk region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Marta Vvedenska (Huley)

mARTA VVEDENSKA (HULEY)

deported in 1950 to the Tomsk region

We bought a hut. It implies that we still had something with us, some carpet, some kapa.* We must have sold things like that. But the hut was boarded up; nobody lived there. There was one room only, and nothing else. It had two beds. Two brothers slept on the same bed, and my mother and I slept on the other one. There was a table in the middle. At the entrance, there was an oven, or a stove rather, you know, like they have in villages. We cooked something there. There was a small kitchen garden near the house. Some pumpkins were growing there.

*kapa — blanket

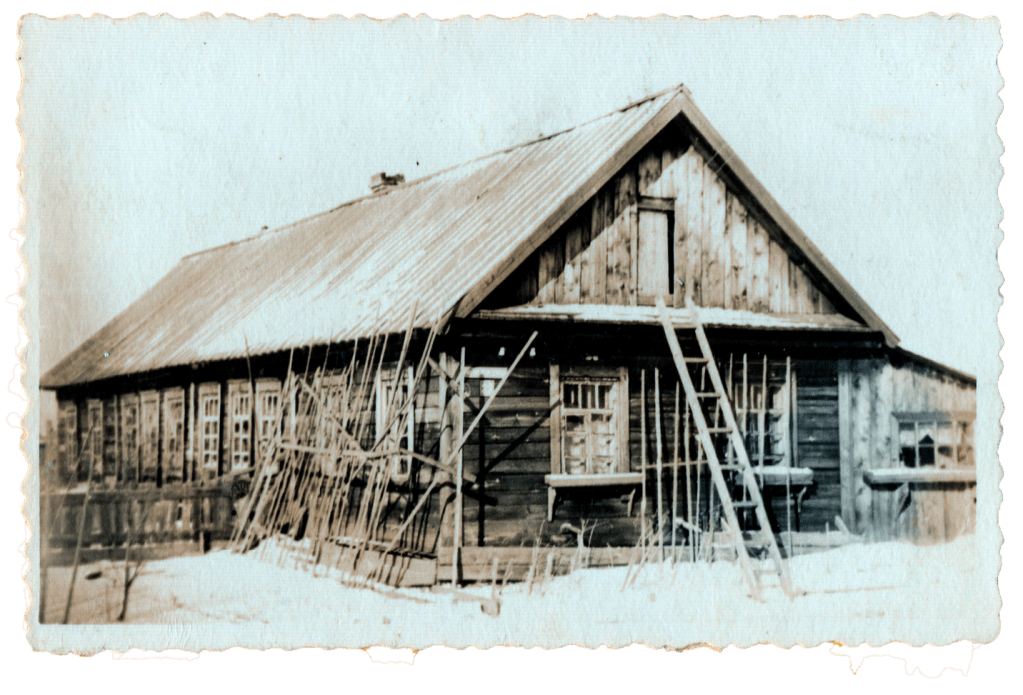

House of Special Settlers, Khor village in the Khabarovsk region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Natalia Boyko (Pokhodzhai)

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

Heads of institutions that used the labour of special settlers had to provide them with at least some housing. They were mostly treated as temporary labor, so they did not consider it necessary to take care arranging at least the minimum living conditions. For a long time, special settlers have lived in poorly equipped barracks, in former wood dryers, barns, and dugouts. The average standard limit of living space per person was not up to 1.9 square meters. Sometimes, it was much less. Those who were not in demand, mostly single people of working age or mothers with many children, had to take care of housing on their own. Over time, some began to build new houses, having previously obtained special permission from the commandant. The status of special settlers implied the restrictions on movement, only within a 3 kilometers radius from their place of residence. Violations of that rule, as well as escape, entailed administrative or criminal penalties. People whose passports were confiscated and special certificates or passes were issued instead were firmly tied to their place of residence and work.

Special settler Yaroslav Dyakon near his house, Zyryanske village in the Tomsk region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Vira Pilyanska (Dyakon)

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

These photos speak a lot about the living conditions and circumstances in which the deportees stayed, but they do not explain much about their feelings and attitude to that place. How did the people who lived in these houses feel? Were they warm, were they scared, did they feel safe? Were there any places that were especially important to them? We can learn about this only from the recorded stories of eye-witnesses, or take wild guesses looking at the poor low huts. For example, in a photo where a woman is standing next to the house where she lives, the incomparably small size of the house catches the eye – the person’s figure next to the house seems disproportionate, too large.

Collected in one category and torn from the context of the personal stories of individuals, these houses become a typological representation of the living conditions of persons who were deported to Siberia. In this way, vernacular photography plays a dual role: it tells the story of a certain person and provides information about the broader context of the existence of a certain social group. They are memories from the family archive and historical evidence.