HOLIDAYS

Khabarovsk and Omsk regions, Tomsk city

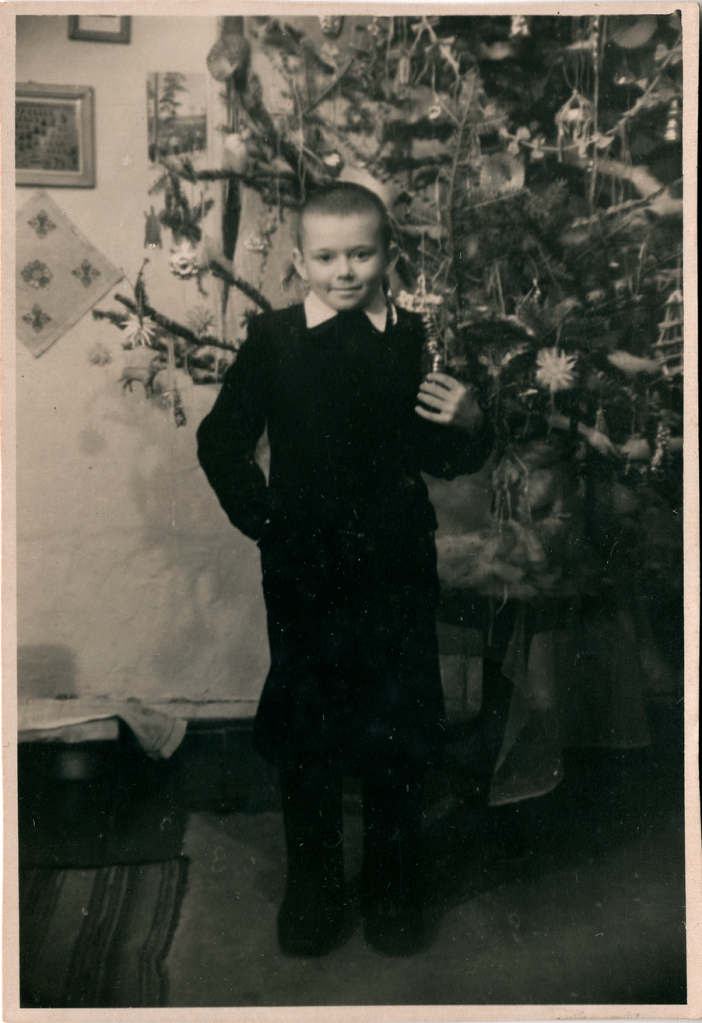

Roman Skytskyi near the Christmas tree, Khor village in the Khabarovsk region, 1956

Source: Private archive of Roman Skytskyi

bOHDAN KOSTELNY

deported in 1947 to the Kemerovo region

But we went to our barracks and sang the carols (we didn’t go to the Tatars to sing carols). They came to the school, and the teacher, Polzova was her name, [asked]: ‘Well, did you go to praise God?’ — ‘Yes, we went to praise God.’ ‘How much did they give you?’ — ‘A ruble, or three.’ ‘Oh, so much!’ And we were expelled from school. But my father went to the school principal and they took us back.

Mykola and Vira Tsvyk (first and fifth from the right) with friends, during Easter celebration, Tomsk, 1959

Source: Private archive of Vira Tsvyk (Borovets)

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

Despite the fact that religious holidays were not an official holiday in the Soviet Union, deportees from Western Ukraine tried to celebrate them according to traditions. So, at Christmas holidays, we would sing Christmas carols and shchedrivka songs in a family circle or together with neighbors in a barrack. We seized opportunities to cook the appropriate dishes. After Stalin’s death, such celebrations assumed a different atmosphere. The special settlers were in high spirits and hoped to return home soon. Financial opportunities have somewhat improved. That’s why the feasts were not as miserable as before, and people dressed in the best clothes, and decorated their homes with embroidered draping and tablecloths.

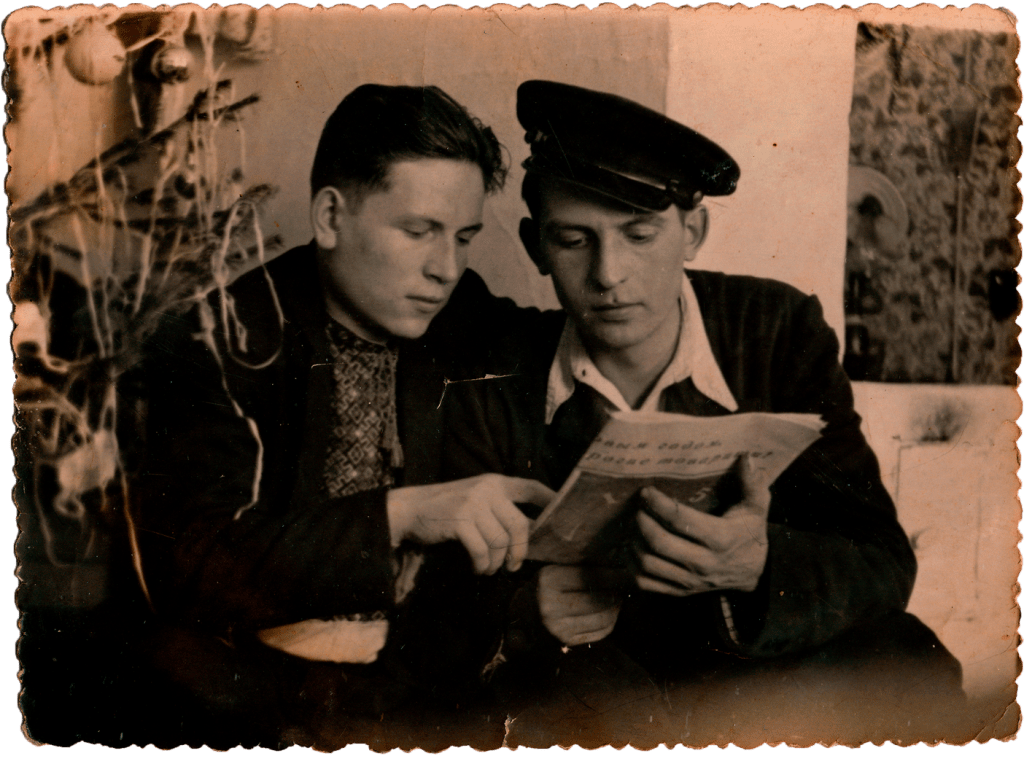

Fedir Volsky (left) with a friend during the New Year celebrations, Omsk region, 1950s

Source: Private archive of Lidia Stanitska

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

In vernacular photographs of festive events, whether secular or religious, we often see a typical representation of rituals and holidays as a social construct. The number of storylines behind is quite limited and rather predictable, such as the photos with Christmas tree in the background, photos at a table set with festive dishes, group photos with the newlyweds, with a birthday person, and the like.

The challenge in reading vernacular photographs more deeply may come from their standard image nature. Therefore, it impedes a more detailed analysis. Researchers of photography say that family photos offer conventional illustrations of how it should be, rather than showing some details of the actual relationship between family members. Therefore, when we look at pictures of people separated from us by decades, we have to rely on eyewitness accounts and how they read semiotic meanings.

On the other hand, such photos were often taken by a family member, and then either found their permanent place in the album of the same family, or sent to relatives. Deportees often sent photos to relatives who were in Ukraine or in Gulag camps. Therefore, according to their photo owners, they were intended for important eyes. That is why the opacity of the vernacular archives serves as a kind of protective layer from prying eyes, including researchers.