family

Kemerovo and Tomsk regions

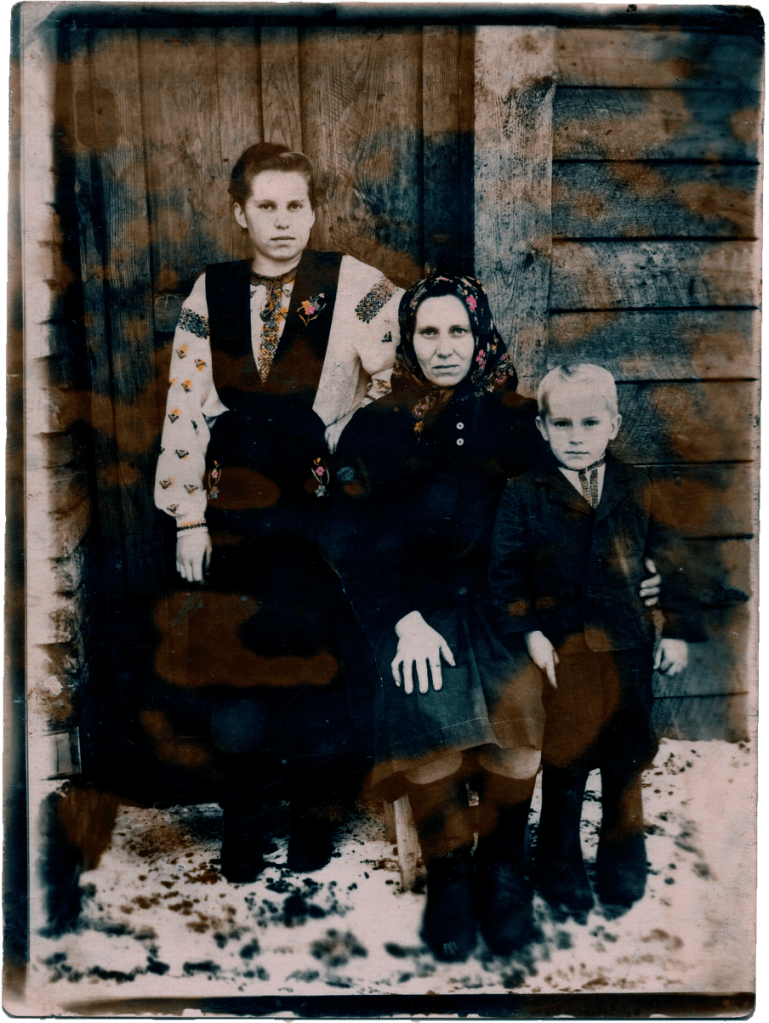

Maria Popovych with her children, Olha and Ivan, Kyselyovsk city in the Kemerovo region, early 1950s

Source: Private archive of Lyudmila Zborovska (Syd)

LYUDMYLA ZBOROVSKA (SYD)

from a deported family to the Kemerovo region in 1947

My grandfather, my mother’s father, Popovych Ivan Mykhailovych, was in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and died in battle. For that, my grandmother with her three children were deported. My grandmother is Popovych Maria Ivanivna. The three children are: the eldest daughter Olha, the middle daughter is my mother, Maria, and the youngest brother is Ivanko. My mom (she was 8 years old) jumped out of the cart. To be more specific, they arranged some distraction, and she jumped out of the cart and ran away. That’s what I know.

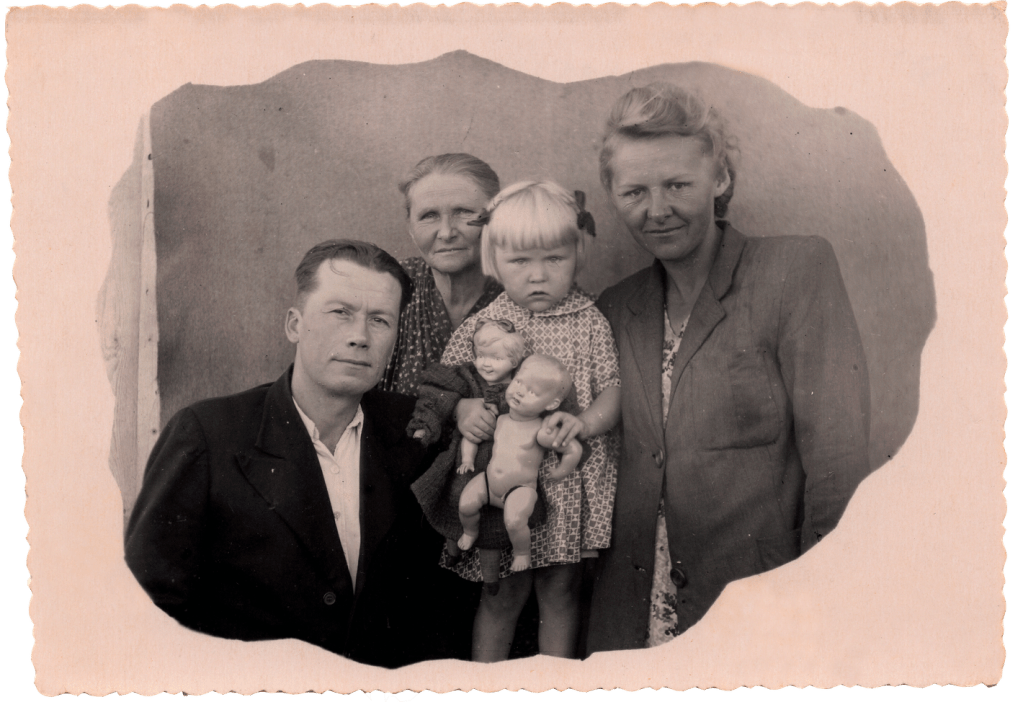

Mykhailo and Olha Tymovchak with their daughter, Lesya, and Yulia Barabash, Olha’s mother, Cherdaty village in the Tomsk region, 1952

Source: Private archive of Lesya Tymovchak

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

The Bolsheviks used “family hostage” from the first days of their coming to power. In 1934, the practice was legitimized when the respective provisions were included into the criminal codes of Soviet republics. The personalized list of those who were subject to punishment for belonging to the families of actual or alleged opponents of the Soviet regime was determined at the first stage of mass deportations from Western Ukraine, in 1940-1941. The list includes a father, a mother, a wife, children, a father-in-law, a mother-in-law, and siblings of a person labelled a ‘traitor to the homeland’. Their property was subject to confiscation. Minors were ‘humanely’ allowed to be deported together with adults. During 1944 – 1953, the practice continued. It was primarily about the so-called “OUN members,” such as members of the families of UPA soldiers and members of the OUN underground, prisoners in the Gulag camps, as well as those who were in an illegal status or died. Later, the families of the kulaks, wealthy peasants, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Anders’ army soldiers, were also deported. The order of the NKVD of the USSR that regulated the details of the deportation of ‘OUN members’ came out on March 31, 1944. The first convoyed special train with deportees left on May 7, 1944 from Zdolbuniv station in Rivne region to Krasnoyarsk Territory. It carried 451 people.

Mykhailo and Kateryna Kostelny, with their children Hanna, Mariia, Vasyl, Bogdan and a niece Olha Shkrermetko, Prokopyevsk city in the Kemerovo region, late 1940s

Source: Private archive of Bohdan Kostelny

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

Our perception of each individual photo in the archive is influenced, among other things, by the sequence in which we review the images and by the general knowledge of what happened in the history of a particular family. For example, this collection has a photograph from the cemetery that shows the same people, except for a woman, whose grave the family must have come to visit. So, looking at the photo where Ms. Olga is still alive, we cannot help thinking about her untimely death, and we can even start looking for signs of misfortune that is about to happen. However, the most terrifying image in this photo is produced by dolls that little Lesya is holding in her hands (at least, it is my impression).

Someone carefully painted the photo from Ludmila Zborovska’s archive by hand, decorating the ornaments on the clothes with different colors, such as children’s embroidered shirts and a mother’s headkerchief. Such interference with the photographic image is typical of its time. Usually, the pictures painted the sky, plants, clothes, or architectural elements in the background. In the studio photos, we can see the painted skin, eyes, and lips of the models. The fact that the author painted embroidery on the shirts and flowers on the headkerchief can be seen as a way to highlight the family’s Ukrainian identity; or these elements were painted simply because they are the most decorative.