FAITH

Chita, Irkutsk, Kyseliovsk

Greek Catholic priest Ivan Yantukh, Chita city, 1956

Source: Private archive of Myroslava Krynytska (Sakharevych)

mYROSLAVA KRYNYTSKA (SAKHAREVYCH)

deported in 1950 to the Tomsk region

It was Chita. When I arrived, I immediately looked for Ukrainians. And then, you know, I went to those Ukrainians, and they say: ‘Yantukh, Yantukh.’ And I say, ‘Yantukh is my uncle, father’s brother.’ I was very pleased. There were two priests, brothers Ivan and Josyf, monks. And the year that I was there, they took great care of me. Ivas was so stubborn, he even was [in prison] and released. One of those [prison governors] said for him, ‘Say something against religion.’ Then he said so sharply, ‘Don’t you dare, or I’ll kill you when you tell me something about religion.’ He was such a fanatic, a kind of religious fanatic.

Greek Catholic priest Mykhaylo Davybida, Irkutsk city, 1957

Source: Private archive of Myroslava Krynytska (Sakharevych)

TAMARA VRONSKA

historian

At special settlements, adherents of different religions deported from Western Ukraine tried to follow religious rites. They gathered together in barracks and organized prayers; older family members taught children to pray. Greek Catholics were assisted in all that by priests, also deported. Due to the ban on performing religious rites, they worked on an equal footing with everyone. In some areas, commandants first turned a blind eye to the fact that priests were, after all, ‘conducting the service.’ Eventually, the indulgence ceased. Ukrainian researcher Oksana Kis, who studied the issue of religious practices of women political prisoners in the Gulag camps, emphasized the unique experience of women’s worship. ‘In fact, never before would those women and girls be admitted to perform a central ritual role in a Christian liturgy, such as priests or deacons’. A similar situation was found among women in special settlements.

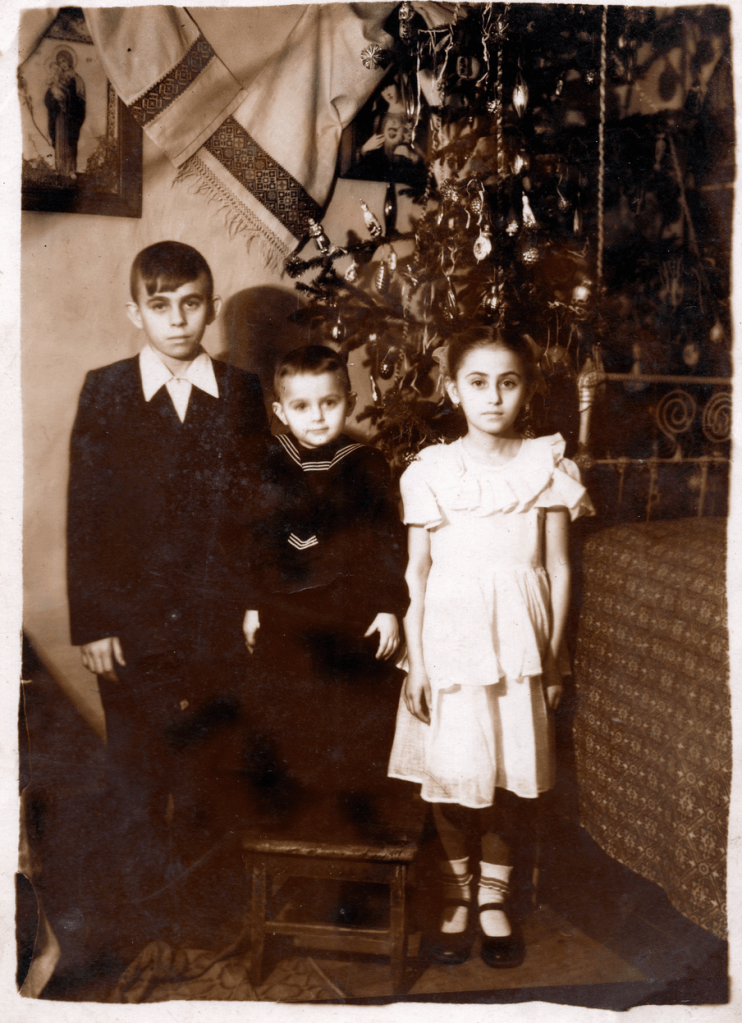

Roman, Bohdan, and Halyna Romaniv, Kyseliovsk town in the Kemerovo region, 1959

Source: Private archive of Maria Moravska

LIA DOSTLEVA

cultural anthropologist

Three small children, dressed in festive clothes, lined up in front of the camera. The older boy stares intently and calmly at the camera, his uneven fringe strayed to the side. The girl has earrings in her ears, a braided ribbon in her hair, and brand new shoes contrast with white socks. The youngest boy is standing on a chair. In the background, there is a Christmas tree richly decorated with glass figures, among which we can see several Santa Clauses, Snow Maiden, icicles, and pine cones. Icons embellished with embroidered drapes hang on the wall. Looking at the many details in this photo, you can never understand that it was made in a special settlement. This is because each individual vernacular photograph may not have all (or sometimes none) of the visual markers by which we attribute a photograph as documenting a particular event, place, or period. However, we cannot separate the image from the conditions in which it was created and the circumstances in which it circulated.

Despite all the efforts of the photographer to create a cozy home-like atmosphere of the Christmas holidays and to leave out the difficult living conditions in Siberia, we can still discern some things. Sharp deep shadows and a bright light source on the left tell us there is a window just behind the left border of the frame. So, if we assume that the Christmas tree is most likely in the corner of the room, and the bed is at the wall, it becomes clear that the room where the family is photographed is really tiny.